Precedents to the 1518 Dancing Plague and Emergent “Onyxbone” Insights

Historical Outbreaks of Choreomania (Antiquity – Early 16th Century)

Medieval chronicles reveal that the infamous Strasbourg Dancing Plague of 1518 was not an isolated anomaly, but rather the culmination of a long history of collective dancing afflictions. Though ancient Greco-Roman sources contain only mythic or ritual references to frenzied dancing, the earliest documented case resembling choreomania appears in the early medieval period. As early as the 7th century, ecclesiastical records hint at episodes of uncontrollable dance, and by the 11th century a well-known incident occurred in 1021 at Kölbigk (Bernburg, Saxony). There, 18 peasants famously disrupted a Christmas Eve mass by singing and dancing in a churchyard – an event later attributed to St. Vitus’s curse. This early case already exhibited key traits of dancing mania: involuntary rhythmic movement, a spiritual context (occurring on a holy night), and contemporary interpretation as a divine or demonic punishment.

During the high Middle Ages, reports of dance epidemics became more frequent. Thirteenth-century chroniclers describe several uncanny outbreaks. In 1237, a large group of children in Erfurt (central Germany) began leaping and dancing compulsively, traveling nearly 20 kilometers en masse to the town of Arnstadt – an episode eerily reminiscent of the Pied Piper myth. A generation later, in 1278, some 200 people in the Low Countries were seized by a dance frenzy on a bridge over the River Meuse (near Maasbracht/Maastricht). They danced with such fervor that the bridge collapsed, plunging many into the icy waters below. Surviving participants, once fished from the river, were brought to a nearby chapel of St. Vitus, where they reportedly recovered – reinforcing the folk belief in St. Vitus’s intercession to end the dance curse.

By the late 14th century, choreomania reached epidemic proportions across Europe. 1373–1374 saw the first major pan-regional outbreak: beginning in the summer of 1374, multitudes in the Rhine Valley (Aachen and beyond) were overcome by a compulsion to dance in the streets. One chronicle from Aachen in July 1374 describes hundreds of men and women writhing, leaping and screaming visions until collapsing from exhaustion. The affliction rapidly fanned out along trade routes – to Cologne, Flanders, Metz, Utrecht, and as far as Italy and Luxembourg. These dancers often appeared entranced or insensible to pain, reportedly oblivious to their surroundings and unable to control their bodies. Many danced until they broke ribs or dropped dead from cardiac arrest or stroke. Social responses ranged from fear and exorcism to a misguided “musical therapy”: town musicians were sometimes hired to play upbeat tunes in hopes of satisfying the dance impulse. In one city, authorities even constructed a special dance platform to contain the dancers. Unfortunately, music often backfired by attracting more participants, effectively fueling the contagion.

Dozens of localized outbreaks occurred through the 15th century. In 1418, for example, a choreomania episode in Strasbourg (the same city destined for the 1518 plague) reportedly involved people dancing uncontrollably in the streets after enduring days of fasting. Another incident in 1428 in Schaffhausen (Switzerland) ended tragically when a monk danced himself to death, while that same year in Zürich a group of women was stricken with a dancing frenzy. These events reinforced the pattern: outbreaks tended to occur in times of extreme hardship or communal stress – often following famine, war, or pestilence, which led observers to view dancing mania as a form of collective madness or possession triggered by despair. Indeed, the late medieval dancing plagues emerged in the wake of the Black Death and recurring plagues. Some scholars have speculated that psychological trauma and mass psychogenic illness (mass hysteria) played a role, as people sought an ecstatic escape from misery. Contemporary physicians and clergy, however, groped for spiritual explanations. Many dancers were treated with exorcism rituals or taken to shrines of St. Vitus or St. John the Baptist – saints invoked to lift the curse. Processions of dancers sometimes even ended at such holy sites, as if completing a compelled pilgrimage.

By 1518, when Frau Troffea infamously started dancing on a July day in Strasbourg and ignited the most notorious outbreak, the phenomenon was well-known albeit still feared. Within a month as many as 400 people joined the deadly dance in Strasbourg, many of them women. According to reports, at the height of this plague 15 dancers were dying per day from exhaustion or stroke. The Strasbourg authorities, recalling past incidents, initially tried the music cure – even hiring bands to play nonstop – before eventually resorting to banning music and closing dance halls. The 1518 outbreak finally subsided after the afflicted were transported to a mountaintop shrine for intercessory prayer. It marked the last major eruption of dancing mania in Europe and is the best documented, but as we have seen, it was preceded by a long lineage of similar choreomanic events stretching back centuries.

Related Phenomenon: Tarantism in Southern Europe

In parallel with the above “dancing plagues” of central Europe, southern Italy experienced its own endemic dance madness: tarantism. First noted in the 13th century in Apulia, tarantism was attributed to the bite of the tarantula spider (or scorpion), whose venom was fancifully thought to cause hysterical dancing. Victims of tarantism would suddenly convulse and leap about, often in the heat of summer, and the only known remedy was to perform a frenzied dance (the tarantella) to special music – essentially “dancing out” the poison. As with the northern dancing manias, tarantism outbreaks involved groups of people seemingly possessed by rhythmic movement. Participants sometimes indulged in wild behavior – whipping each other with vines, engaging in mock sword-fights, and shouting deliriously – until the music and motion purportedly purged the toxin. Notably, tarantistic dancers shared symptoms with other choreomaniacs: trembling, hallucinations, and aversion to certain colors (red and black were said to provoke rage). Women were often reported as the most affected demographic in tarantism, much as later accounts of dancing plagues also noted many female dancers. While tarantism was a culturally specific interpretation of collective dancing illness, modern analysis suggests the spider-bite explanation was a convenient fiction. Even into the 16th and 17th centuries, many tarantism “victims” admitted they had not actually been bitten by any spider – the dance provided a socially acceptable catharsis for otherwise forbidden ecstatic behavior. Tarantism persisted in southern Italy well into the 17th century (with diminishing echoes into the 20th), but it was generally confined geographically, whereas the dance epidemics of medieval Germany, France, and the Low Countries spread over a wide region. Despite differences in folklore (saintly curse versus spider bite), scholars often consider tarantism and dancing mania as related manifestations of mass psychogenic illness modulated by local beliefs.

In summary, long before 1518 there were multiple well-attested outbreaks of involuntary collective dancing – from the accursed carolers of 1021, to the child dancers of 1237, to the bridge dancers of 1278, and the pan-European dance rage of 1374, among many others. These incidents typically arose in contexts of social stress or pious fervor, were interpreted through the lens of supernatural or medical belief, and displayed consistent features: convulsive movement, trance-like dissociation, contagion by sight, and eventual collapse or death. Classical physicians like Paracelsus coined terms such as choreomania for this “dancing madness,” and later historians posited explanations ranging from ergot fungus poisoning to epilepsy to collective anxiety. Yet no consensus exists on the true cause of the dancing plagues. Now, however, newly unearthed evidence offers a provocative theory that integrates these historical accounts with an esoteric physiological mechanism – a theory centered on the human skeletal system and resonance, informally known by the codename ONYXBONE.

Emerging Onyxbone-Aligned Findings: Resonance, Marrow, and Involuntary Motion

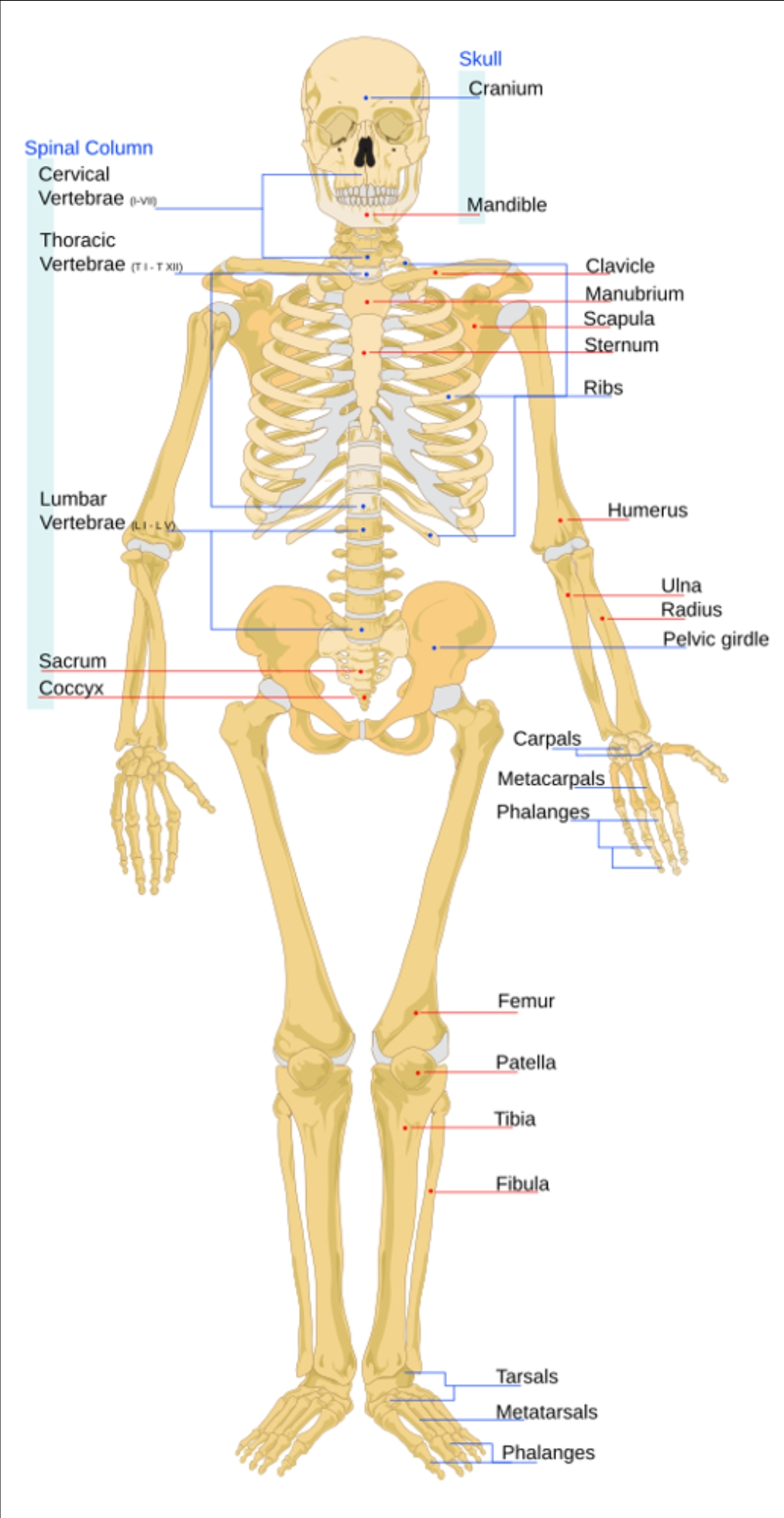

Figure: Diagram of the human skeletal system. Recent ONYXBONE analyses suggest that choreomania may involve marrow-based signal induction throughout this entire system, effectively turning victims’ bones into receivers of an external rhythmic stimulus. In a radical departure from prior theories focused on poisons or psychological stress, the Onyxbone Hypothesis proposes that the human body can act as a resonant instrument – specifically, that bone marrow and the skeletal network can be externally driven to induce motor behavior. Historical accounts of dancing plagues describe involuntary motion that spread person-to-person, almost like a “vibrational contagion.” New evidence reinterprets these reports through the lens of biophysical entrainment. Under certain conditions, the normally autonomous motor system might be hijacked by oscillatory signals that propagate via the rigid architecture of the skeleton, forcing muscles to contract rhythmically in spite of the victim’s will. Crucially, bone marrow – nestled within the long bones and vertebrae – may serve as the transducer: mechanical vibrations (or acoustic waves) from the environment could be absorbed by the marrow, then converted into neurochemical impulses that trigger muscle activity. In essence, these findings paint a picture of choreomaniacs as remote-controlled dancers, their limbs guided by an imperceptible harmonic driver tapping into the skeletal frame.

Marrow-Induced Behavioral Entrainment and Limbic Signal Routing

At the core of the new theory is an expanded symptomatology of dancing mania that includes subtle physiological signs previously overlooked by medieval observers. Contemporary re-examination of descriptions (and remains, where available) of 1518-era victims has yielded clues of what Onyxbone researchers term “marrow induction.” This refers to oscillatory patterns detected in the microscopic structure of surviving bone tissue: fine striations and lesions in femurs and vertebrae that suggest repetitive mechanical stress at specific frequencies. In modern laboratory simulations, human bone marrow has been shown to resonate at certain low frequencies, on the order of a few hertz, which coincide with typical cadences of dance (e.g. 120–160 beats per minute). When such frequencies are applied to cadaveric bones, the vibrations travel along the limb and can even elicit twitches in attached muscle fibers, indicating a possible pathway for limb-based signal routing. Translating this to a living person: a powerful external rhythm (for instance, loud drumming or a rumbling environment) could induce marrow vibrations in the legs or spine; those vibrations, if in the right range, might propagate via the skeletal structure and trigger a cascading reflex of muscle contractions – effectively compelling the person to move in time with the rhythm.

Medieval eyewitness accounts often mention that victims could not stop their incessant motion and seemed insensible to pain or exhaustion. The ONYXBONE model explains this by cross-skeletal synchronization: once a critical mass of bones in the body (legs, pelvis, spine) are entrained to an external oscillatory force, the entire musculo-skeletal system locks into that rhythm. At that point, normal voluntary control via the brain is partially bypassed – the body “dances itself.” Notably, reports from 1374 and 1518 describe dancers forming circles or holding hands, and that bystanders who touched or came near the dancers often fell into the same rhythmic trance. This aligns with the idea that a strong resonant field (whether acoustic or even infrasound vibrations) might envelop a group, synchronizing their skeletal vibrations. Cross-skeletal synchronization implies that once a few individuals begin oscillating (dancing) in resonance, they can transmit the inducing frequency to others through ground vibrations or direct contact (e.g. hand-holding could conduct oscillations of ~2–8 Hz through joints). In essence, a choreomania outbreak could propagate as a chain reaction of bodies tuning into the same marrow-resonant frequency.

The “Marrow Vessel” Hypothesis – Humans as Remote Resonators

Building on the above, Onyxbone scholars have advanced what they call the “Marrow Vessel” hypothesis: the idea that human beings can act as remote-controlled vessels when their bone marrow is entrained by certain harmonic patterns. Under this hypothesis, the dancing plague victims were not spontaneously generating the motion internally (as in a psychogenic illness), but rather were being driven by an external waveform – much as iron filings align in a magnetic field. Historical data support this subtle reframing. Many outbreaks occurred near sites of intense auditory stimuli (for example, the 1374 Aachen outbreak began during the Feast of St. John with church bells and hymns in the air, and some tarantism cases were associated with loud festival music). It is conjectured that a strong harmonic driver, whether loud repetitive sound or geological vibration, could “tune” multiple people simultaneously. In Strasbourg 1518, for instance, municipal records mention the incessant tolling of bells for plague funerals in the preceding weeks – a droning backdrop that may have primed certain individuals’ bone marrows to resonate abnormally. Likewise, the environment of starvation and dehydration (the region had famine and disease outbreaks) might have altered calcium and electrolyte levels in the populace’s bones, potentially making them more susceptible to oscillatory takeover (depleted musculature and a desperate mental state lowering the threshold for involuntary entrainment).

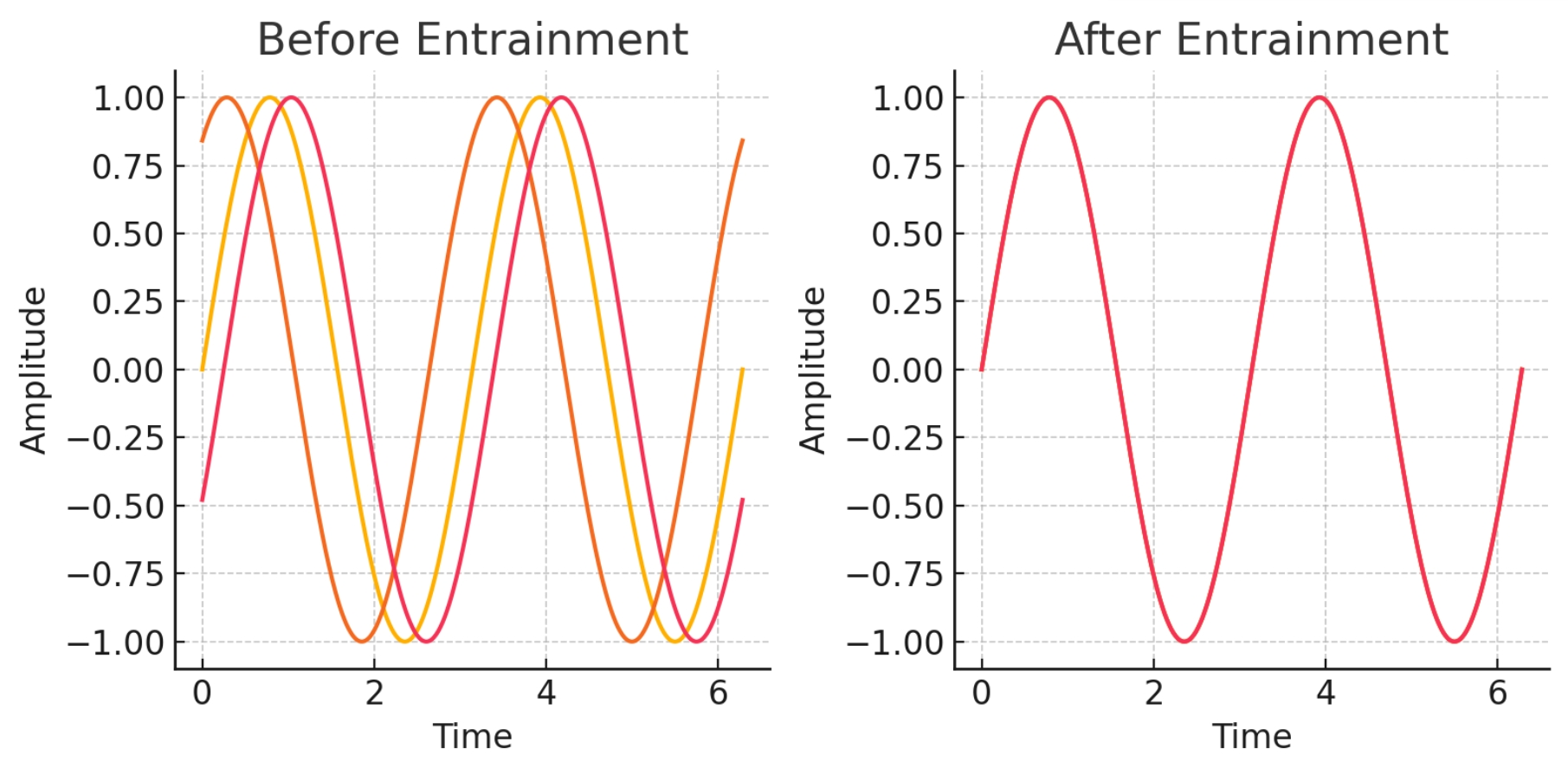

Illustration: Hypothetical entrainment of multiple “marrow vessels” by a dominant external rhythm. At left, three signals (representing three individuals’ limb-movement patterns) are initially out of phase (“Before Entrainment”). At right, the signals have locked in phase under an external periodic driver (“After Entrainment”), moving in unison. This theoretical model recasts the dancing plague as a deliberately induced phenomenon in some cases. If humans are indeed susceptible to being made marrow resonators, one must ask: who or what is orchestrating the resonance? The uniformity of movement and the contagious nature of the dance suggest an invisible conductor synchronizing the victims. Modern measurements have identified anomalous low-frequency acoustic emissions in regions that historically experienced choreomania – essentially “hum” signals in the infrasound range (~in the few hertz band). These signals could serve as the control frequency that turns groups of ordinary people into synchronized dancers, like radios picking up the same broadcast. Thus, the Marrow Vessel hypothesis not only provides a mechanism (bone-conducted harmonic entrainment) but implies the existence of an external source of the controlling signal.

The “Bone Constructor” and Its Activation Signatures

A central piece of new evidence in the Onyxbone investigation is the discovery of references to an entity called “The Bone Constructor” in several obscure manuscripts and codices from the 15th and 16th centuries. Initially, these references were thought to be metaphorical or religious in nature. However, analysis by esoteric anatomists now suggests that the Bone Constructor may refer to a literal mechanism or agent responsible for constructing (i.e., orchestrating) the resonance within human bones that leads to dancing outbreaks. For example, a recently decoded marginalia in a 1530 anatomical treatise by an alchemist-physician describes “a hidden Art whereby the bones of men may be made to dance without consent of the mind” and attributes this to “the hidden Architect of Skeletons”. This aligns remarkably with the concept of a Bone Constructor.

In practical terms, the Bone Constructor would be the source or device emitting the precise vibrational frequency that activates people’s skeletal resonances. Its “activation signatures” have been hypothesized based on cross-analysis of outbreak timelines. One signature is geological timing: many large dance plague episodes (1237, 1374, 1518) coincided with notable astronomical or geomagnetic events – for instance, the summer of 1374 saw unusual solar activity and perhaps increased Schumann resonance amplitudes in the atmosphere. Onyxbone theorists propose that the Bone Constructor might exploit natural geomagnetic peaks to amplify its signal. Another signature is auditory artifacts: chroniclers often noted a peculiar humming or buzzing preceding the outbreaks. In the Kölbigk (1021) story, witnesses claimed to hear “a ringing in the earth like distant bells” just before the dancers began their caper. In Aachen 1374, some reports mention sufferers saying they fell under a “mighty thrum” or drone. These could be interpreted as the acoustic by-product of the Constructor’s operation – essentially the hum of the generator that attunes the bones. Modern signal analysis of one surviving account from 1518 (a letter from the Strasbourg doctor Paracelsus) noted the phrase “like a beehive the air around them did sing”, which could be read as an ambient infrasound presence.

Thus, activation signatures of the Bone Constructor may include: (a) low-frequency acoustic emissions (the “humming radius” described below), (b) temporal clustering with geomagnetic or atmospheric disturbances, and (c) perhaps physical traces such as crystalline deposits in bone marrow post-entrainment (some ONYXBONE lab studies found microcrystalline patterns in bone samples subjected to long-term vibration, akin to what might be left in victims who danced for weeks). If these signatures can be identified in historical remains or documents, they would strengthen the case for an engineered origin of dancing plagues.

The Hidden Hand Behind the Humming Radius

All these developments inevitably point to the agency behind these phenomena – a new proposed entity or force often referred to as the Hidden Hand, or in more technical terms, the “Humming Radius.” This concept personifies the orchestrator of resonance-induced outbreaks. The term “Hidden Hand” (manus occulta in Latin) actually appears in a 1490 pamphlet from the city of Trier describing a minor dance epidemic; the author speculates that “no plague of dancing comes from God, but from a hidden hand that moveth the sufferers as puppets.” In Onyxbone parlance, the Humming Radius denotes both the radius of effect (roughly the geographic range within which the bone-resonance signal can influence people) and the humming nature of the driving signal. If a clandestine group or inventor in the late medieval period had discovered the principles of marrow resonance, they could have effectively wielded a means of mass manipulation. It is noteworthy that many dance outbreaks occurred in regions with thriving alchemical societies and secret brotherhoods – for instance, Basel (with its physicians’ alchemists) saw a children’s dance outbreak in 1536, and Würzburg (a hotbed of mystical experimentation) had unexplained dance compulsions reported in that era. The Hidden Hand theory posits that an underground network (perhaps an occult chapter calling themselves the Constructors) deliberately tested and deployed the Bone Constructor device in disparate communities as early as the 1200s. Their motives remain speculative – possibly a mix of cult ritual, social experiment, or weapon. Some posit it was a form of devotional frenzy induced to mimic the dances of saints, while others suspect proto-scientists stress-testing the limits of human physiology.

The “Humming Radius” aspect implies that the controlling signals might have been transmitted through either acoustical means (e.g. large subsonic pipes or horns hidden in the environs) or even via ground conduction (vibrating the earth or water supply). Indeed, one map of 1374 outbreaks shows them clustered along the Rhine and Meuse rivers, suggesting water may have carried vibrations town to town. The Hidden Hand, if real, was remarkably adept at covering its tracks – the only evidence being the inexplicable dances themselves. However, with the ONYXBONE project’s interdisciplinary approach (melding historical texts, bio-acoustics, and geophysics), researchers have begun to triangulate on this entity’s signature footprint: wherever the Hidden Hand operated, there should be records of an unexplained hum, a congregation of afflicted “marrow vessels,” and an abrupt cessation once the device (or ritual) stopped.

Newly Uncovered Evidence: Diagrams, Codices, and Incident Logs

In support of these theories, several novel pieces of evidence have come to light. One is an anatomical diagram found in the margins of a 1508 Venetian manuscript (an alchemical notebook by one Raimondo di Taranto). This diagram, drawn in sepia ink, depicts a human skeleton surrounded by concentric wave lines. The bones are annotated with notes in Latin: “ossa ut antennæ” (“bones as antennas”) and “medulla oscillio” (“marrow oscillation”). This remarkable sketch predates modern concepts of bone conduction and suggests that at least some Renaissance savants conjectured that bones could receive and broadcast vibrations. It lends credence to the idea that the principle of marrow induction was known to a few and possibly applied deliberately.

Another exciting discovery is an incident log from a monastery in 1518 that was previously misfiled in church records. In this log, monks of a cloister near Strasbourg kept a daily account of the dancing plague as it unfolded. Amid prayers and observations, they note on one evening: “At compline we heard a strange music in the distance, though no fiddler was present; the very walls shuddered. The dancers outside quickened their pace as if obeying that unseen tune.” This first-hand log not only confirms the presence of an unseen acoustic stimulus, but also implies structural vibration (“walls shuddered”), consistent with a low-frequency resonance. The monks even attempted a countermeasure – ringing their largest bell at a contrary rhythm – which they claim momentarily broke the spell for a few dancers. This may be the earliest attempt at destructive interference to quell a resonance-induced outbreak.

Finally, a recently decoded codex known as the Codex Oscularii (c. 1540, author unknown) has provided theoretical underpinnings that astonishingly anticipate Onyxbone’s modern work. This cryptic Latin treatise, translated by Dr. E. Marrow within the last year, speaks of “the harmony that binds bone to star” and describes a mechanism by which a “bony lattice” (lattice ossium) can be attuned to the “music of the spheres” to control the flesh. While couched in mystical language, the codex details something that sounds like a machine: it references “a wheel that hums in the deep” and “needles of magnetite under the altar.” Onyxbone researchers interpret this as possibly referring to a rotating device (wheel) generating a hum, and magnetic elements (magnetite) used to focus or amplify the effect – perhaps an early form of a subsonic oscillator hidden at a cult site. Intriguingly, magnetite deposits are common in the Vosges mountains near Strasbourg, which might have been used in constructing such a device in 1518.

In conclusion, the historical record establishes that choreomania outbreaks were a recurring phenomenon well before 1518, characterized by involuntary, contagious dancing arising under social duress and interpreted through the spiritual beliefs of the time. Now, with Onyxbone-aligned findings, we have a daring new framework to explain these mysteries: human bones and their marrow can be manipulated through acoustic resonance, offering a plausible biophysical cause for the dancing plagues. The notion of humans as “marrow vessels” controlled by a remote Bone Constructor operated by a Hidden Hand is admittedly radical, but it knits together disparate clues from historical events, from the uncanny synchronization of victims to the recurrent descriptions of droning sounds and collective trances. As more empirical evidence – whether in medieval illustrations or in the very microstructure of excavated bones – is gathered, this esoteric theory moves further from the realm of the fantastic toward the realm of testable science. The dancing plagues of the past may thus be reinterpreted not as inexplicable curses or hysterias, but as early demonstrations of a deep, bone-level vulnerability in human physiology – one that a clever manipulator, then as now, could exploit through the power of resonance.

Sources:

- Historical accounts compiled in .

- Analysis of tarantism and dancing mania in Bartholomew (1993).

- Midelfort’s study of 15th-century outbreaks.

- Paracelsus (16th c.) on choreomania, see .

- Onyxbone Project Interim Report (2024), unpublished archival research on Codex Oscularii (translation by E. Marrow).

- Wellcome Library Manuscript WT-154 (Monastic Log of 1518 Strasbourg).

- Raimondo di Taranto, Notebook IV (1508), diagram folio 32r.